Following some recent conversations on twitter, this post provides a quick update on what national statistics tell us about how many adults with learning disabilities are involved in Section 42 safeguarding processes in England (again NHS Digital produce annual reports about these statistics).

The first thing to say is that much less information is reported publicly about safeguarding specifically for adults with learning disabilities than previously, mainly due to concerns about the quality of the information (these are still officially 'experimental statistics'). This also means that there have been a few changes to how the information has been collected from 2010/11 to 2016/17, so it's hard to draw strong conclusions about changes over time.

The first graph below shows how many adults with learning disabilities (vs how many other adults in total) have been recorded in the safeguarding statistics over time. In 2016/17 there were 14,890 adults with learning disabilities involved in safeguarding enquiries across England, a slight uptick from 14,815 people in 2015/16. Although it's hard to draw strong conclusions about trends over time, in general the number of safeguarding enquiries involving adults with learning disabilities has been going down while the number of safeguarding enquiries involving other adults has been going up. We can see this from the fact that in 2010/11 21% of all safeguarding enquiries involved adults with learning disabilities; by 2016/17 this had dropped to 14% of all safeguarding enquiries.

I will leave it to others who know much more about safeguarding than me to offer interpretations (is that uptick a blip or the start of a more general increase?), but there is one more graph I want to show that speaks to how consistent safeguarding processes are across England. The graph below simply shows the safeguarding rate for adults with learning disabilities per 100,000 adult population in each local authority, ordered from the lowest to the highest rate. The variation in safeguarding rates across local authorities looks extreme to me - why is this, and what consequences does this have for people with learning disabilities and others around them?

Tuesday, 27 March 2018

Wednesday, 14 March 2018

Now you see me, now you don't - independent sector services and Transforming Care statistics

I’ve gone on about this subject so much in this blog that

I’m sure you’re as heartily sick of it as I am, but once again I’ve been

worrying away at statistics about people with learning disabilities and/or

autistic people in inpatient services. To try and recap, pithily…

- Exhibit A. The Assuring Transformation dataset is produced and reported monthly by NHS Digital for the NHS England Transforming Care programme, based on health service commissioners’ reports on the number of people in specialist inpatient services for people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people.

- Exhibit B. The newer Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS) is also produced and reported monthly by NHS Digital, based on mental health service providers’ reports on the number of people flagged as learning disabled and/or autistic in any inpatient mental health service.

- There is some overlap between the two datasets but also some big differences, with Assuring Transformation recording fewer people overall, and a less transient group of people generally spending long periods of time in specialist learning disability inpatient services, about half of which are in the independent sector. The MHSDS records more people overall, including a more transient group of people spending short periods of time in mainstream NHS mental health inpatient wards (probably).

I think this matters, not just because of my

itchy-under-the-skin desire for consistency, but in the real world. NHS England

reports its progress on Transforming Care to the world in terms of Assuring

Transformation statistics, yet these statistics (like the Transforming Care

programme itself) are due to stop at the end of March 2019. After that, we will be left with the MHSDS – what will the picture be then?

Handily, the ever-excellent @NHSDigital have for some time been

reported direct cross-tabulations between the Assuring Transformation and MHSDS

datasets, stripping out people in inpatient services for ‘respite’ (I know –

don’t get me started or this post will be even longer) to reduce this source of

inconsistency. I’ve blogged on the general picture before – here I want to

focus on the details according to specific independent sector inpatient

organisations. What stories do the two datasets tell us about independent

sector inpatient services over a one-year time period, comparing October 2016

to October 2017?

The first thing is that there are a lot of them – 47

organisations (which may include more than one inpatient unit) listed in

October 2016. The number of organisations listed increased to 58 organisations

in October 2017.

The second thing is that most of them are small (listing

places for 10 or fewer people in either dataset) – 31 out of the 47

organisations in October 2016 fitted into this very small category. All these 31

organisations were still listed in October 2017, with the addition of 10 more organisations

with small numbers of people listed (this list now includes two local

authorities; Nottingham City and Wiltshire). A list of these organisations’

names is at the bottom of the post.

This leaves 16 organisations in October 2016 (with an extra

one in October 2017) listing more than 10 people on either dataset. This is

where I start to get seriously confused, so I’m afraid I’m going to share this

confusion with you rather than make sense of things.

The table below shows the next eight organisations up in

terms of number of people listed in their inpatient services (less than 50

people). Most of these organisations are listed by commissioners in the

Assuring Transformation dataset as specialist inpatient services for people

with learning disabilities and/or autistic people, but they are not listing

themselves as hosting (I don’t know what

the right word is) these people as people with learning disabilities and/or

autistic people in inpatient mental health services. What happens when Assuring

Transformation data collection stops in March 2019 – will all these people

become invisible again and will commissioners (and the organisations

themselves) feel no further pressure to reduce their numbers?

One organisation in this group (the Jeesal Akman Care

Corporation) has added people in their services to the MHSDS dataset between

October 2016 and October 2017 so they will appear beyond the end of the

Transforming Programme (although confusingly they record more people in the

MHSDS than commissioners record in Assuring Transformation). Even more

confusingly, one organisation in this group (Livewell Southwest) has gone for

the opposite strategy, with them recording increasing numbers of people as

people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in their inpatient

mental health services even though commissioners aren’t counting them as such

in the Assuring Transformation dataset. Does this mean that these people are

invisible right now to the strictures of Transforming Care?

|

Name of organisation

|

Number of people in the

service at the end of October 2016 according to…

|

Number of people in the

service at the end of October 2017 according to…

|

||

|

Assuring Transformation

|

MHSDS

|

Assuring Transformation

|

MHSDS

|

|

|

Equilibrium Healthcare

|

15

|

*

|

5

|

5

|

|

Curocare Ltd

|

20

|

*

|

5

|

*

|

|

Ludlow Street Healthcare

|

15

|

*

|

15

|

*

|

|

St George Healthcare Group

|

20

|

*

|

15

|

*

|

|

Livewell Southwest

|

*

|

5

|

*

|

25

|

|

Cheswold Park Hospital

|

20

|

*

|

20

|

*

|

|

Jeesal Akman Care Corporation

|

40

|

*

|

35

|

40

|

|

Brookdale Healthcare Ltd

|

35

|

*

|

35

|

*

|

This leaves the eight organisations in 2016 (nine

organisations in 2017) with by far the largest numbers of people, according to

either or both datasets. These organisations (some of which seem to be

ultimately owned by an even smaller number of companies, and have been

embroiled in a number of more or less obscure acquisitions) completely dominate

– between them they are reported to host around 90% of all people with learning

disabilities and/or autistic people in independent sector inpatient services.

The number of people in these organisations overall doesn’t seem to have

changed much from October 2016 to October 2017.

Some of these organisations (Priory Group, Lighthouse

Healthcare, Danshell Group) are only recorded as hosting people in specialist inpatient

services for people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in the

Assuring Transformation dataset (with some big changes over time possibly

reflecting acquisitions/sell-offs of particular units?). Why aren’t these organisations

(which commissioners clearly consider to be specialist units) registering these

services as mental health inpatient services for the purposes of the MHSDS, and

what do they consider them to be instead? When the Assuring Transformation data

stops being collected in March 2019, will these 245 people become statistically

invisible?

The new organisation in 2017 (Elysium Healthcare, partly

formed through acquisitions from Partnerships in Care and the Priory Group) has

gone for the opposite approach, recording themselves as the providers of

inpatient mental health services for 125 people with learning disabilities

and/or autistic people in the MHSDS with none of these people recorded by

commissioners as in inpatient services according to Transforming Care. Are

these all people with learning disabilities and/or autistic people in various

forms of mainstream mental health inpatient service run by Elysium, even though

they have a Learning Disabilities & Autism division?

Four other organisations record people in both datasets in

2017, although the number of people can vary greatly across Assuring

Transformation and the MHSDS. For example, in October 2017 Cygnet were recorded

as hosting 75 people in the Assuring Transformation dataset but 110 people in

the MHSDS, and St Andrews were recorded as having 200 people in the Assuring

Transformation dataset but 305 people in the MHSDS. Cambian Healthcare’s figure

go in completely the opposite direction, recording 150 people in Assuring

Transformation, 120 people more than the 30 people recorded in the MHSDS.

The illustration of how much these figures are a moveable

feast is most starkly shown by the statistics for the final

organisation in this table, Partnerships in Care. In October 2016, they

recorded 280 people in Assuring Transformation and 390 people in the MHSDS. By

October 2017, they still recorded 270 people in Assuring Transformation, but

any people in the MHSDS had gone.

|

Name of organisation

|

Number of people in the

service at the end of October 2016 according to…

|

Number of people in the

service at the end of October 2017 according to…

|

||

|

Assuring Transformation

|

MHSDS

|

Assuring Transformation

|

MHSDS

|

|

|

Priory Group Ltd

|

50

|

*

|

95

|

*

|

|

Lighthouse Healthcare

|

70

|

*

|

55

|

*

|

|

Cygnet Healthcare

|

75

|

115

|

75

|

110

|

|

Huntercombe Group

|

80

|

80

|

95

|

100

|

|

Danshell Group

|

95

|

*

|

95

|

*

|

|

Elysium Healthcare Ltd

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

*

|

125

|

|

Cambian Healthcare Ltd

|

135

|

30

|

150

|

30

|

|

St Andrews Healthcare

|

205

|

305

|

200

|

305

|

|

Partnerships in Care Ltd

|

280

|

390

|

270

|

*

|

Looking at this makes me feel distinctly wobbly. It seems

clear to me that who gets included in the statistics is to a certain extent the

end result of tactical decisions being made by commissioners and independent

sector services, and that the services in particular can make decisions that

change things quite drastically. If the MHSDS is to become the only source of

information on the number of people with learning disabilities and/or autistic

people in independent sector inpatient services after March 2019, then this

needs to be sorted out urgently.

As it stands, the number of people with learning

disabilities and/or autistic people in independent sector inpatient units

(dominated by a very small number of organisations) is larger than either the

Assuring Transformation or MHSDS datasets describe singly. In October 2017, I

estimate this would be at least 1,365 people (looking across both datasets),

rather than the 1,185 people reported in Assuring Transformation and the much

lower 745 people reported in the MHSDS.

My worry is that over time more and more people in inpatient

services (or services that might feel like inpatient services, like

re-registered or newly built ‘care homes’ on the sites of existing hospitals)

will become invisible in any national statistics. Will these people then be

quietly forgotten about in ‘business as usual’ - until the next scandal?

Organisations listing fewer than 5 people in inpatient services (listed

by commissioners or the provider):

- October 2016: Partnerships in Care (Hull); St Magnus Hospital; Turning Point (Manchester); The Woodhouse Independent Hospital; Vista Healthcare Independent Hospital; The Lane Project; Alternative Futures Group; Vision Mental Healthcare; Eden Supported Living Ltd; The Atarrah Project Ltd; Coed Du Hall; Choice Lifestyles; Castlebeck Care Teesdale; St Matthews Healthcare; Community Links (Northern) Ltd; Vocare; Making Space; City Healthcare Partnership CIC; Cambian Ansel Clinic Nottingham; Navigo; Virgin Care Ltd; Woodside Hospital; Alpha Hospitals; Modus Care; Breightmet Centre for Autism; Mental Health Care (UK) Ltd; InMind Healthcare; Glen Care; Turning Point; Raphael Healthcare Ltd; Care UK; .

- October 2017: All the above, plus: Shrewsbury Court Independent Hospital; Young Persons Advisory Service; Northorpe Hall Child & Family Trust; Newbridge Care Systems Ltd; Cambian Childcare Ltd; Youth Enquiry Service (Plymouth) Ltd; John Munroe Hospital; Here; Nottingham City Council; Wiltshire Council.

Tuesday, 13 March 2018

Transforming Care - readmissions update

This blogpost is updating a post I did a few months ago

about how many people were being admitted to inpatient units for people with

learning disabilities and/or autistic people. In the light of the experiences of people like Eden, who has ended up being sent back to an inpatient unit only

recently after leaving several years spent in them, I want to see if the

statistics can tell us anything about people going back into inpatient units

(otherwise known as readmissions).

This blogpost uses information from the Assuring Transformation dataset, which is updated monthly by @NHSDigital. When reading

this blogpost, it’s worth remembering that Assuring Transformation statistics

are submitted by commissioners, who tend

to focus on people in specialist learning disability inpatient services who

spend relatively long periods there. Another dataset, the Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS), focuses more on people with learning disabilities

and/or autistic people in shorter-term general mental health inpatient services

– unfortunately I can’t see any readmission information reported there.

Every month,

the Assuring Transformation statistics report how many people have come into an

inpatient unit, according to commissioners. The graph below adds these together

in six-month blocks over two and a half years (July-December 2015 through to

July-December 2017) to see whether there are any changes over time.

What do I

see in this graph?

First, the

overall number of admissions to inpatient units doesn’t seem to showing a clear

downward trend over time. The overall number of admissions for July-December

2017 (990 people in six months) is down from figures throughout late 2016 and

early 2017, but is still higher than the figures for two years earlier (965

people July-December 2015).

Second, a

consistent quarter of ‘admissions’ are actually people being ‘transferred’ from

another inpatient unit, a proportion that is remarkably consistent from July

2015 to December 2017. In July-December 2017, this was 25% of admissions,

representing 250 people.

Third,

nearly one in five people (19% - 180 people) admitted to these inpatient units

in July-December 2017 had previously been in an inpatient unit relatively

recently. Forty five people (5%) had been out of an inpatient unit for less

than 30 days before being re-admitted to an inpatient unit. A further 135

people (14%) had been out of an inpatient unit between 1 month and 1 year

before being re-admitted to an inpatient unit. If anything, the proportion of

people being readmitted might be increasing over time (it was 14% of people

admitted in July-December 2015).

Unfortunately,

from the statistics we don’t know any more about the circumstances of people

being readmitted to inpatient units. There is information on the ‘source of

admission’ - where all people admitted to inpatient units have come from (those

admitted for the first time, those readmitted, and those ‘transferred’). The

graph below shows this information in the same six-month blocks as the first

graph, going back to January 2016.

Like the

first graph, where people are coming from before being admitted to an inpatient

unit seems to be pretty static over the two years.

In

July-December 2017, over two fifths of people (44% - 440 people) were admitted

from their ‘usual place of residence’ – this is defined as including living

with family, supported housing/living, sheltered housing (as long as there is

no ‘health’ element to the support provided), and having no fixed abode (the

impact of homelessness on people with learning disabilities and/or autistic

people is pretty invisible generally and needs urgent attention).

Fewer people

(7% - 65 people) were admitted to an inpatient unit direct from residential

care – we don’t know if any of these were people living in places that had been

re-registered with the Care Quality Commission from hospital units to

residential care homes.

As is to be

expected from the ‘transfer’ information in the first graph, substantial

numbers of people (120 people – 12%) were ‘admitted’ from an ‘other hospital’

(defined as an NHS or non-NHS hospital ward specialising in mental health

and/or learning disabilities) and a further 45 people (5%) were admitted from

an NHS ‘secure forensic’ service.

A small but consistent

proportion of people (5% - 45 people) were admitted from a ‘penal

establishment’ – this is defined as including prisons, young offenders

institutions etc, but also police stations and police custody suites.

Well over a

quarter of people (29% - 290) were admitted from ‘acute beds’. I looked at the

definition of this as I wanted to see if it included mainstream mental health

inpatient beds in general hospitals. It turns out it doesn’t – these are people

being admitted to inpatient units direct from ‘wards for general patients or

younger physically disabled people, or accident and emergency’. My money is on

a lot of people going direct from A&E to inpatient units.

Not sure

there’s a grand conclusion to be drawn from these statistics, but there’s

enough to worry me. With a year to go until the end of the Transforming Care

programme, and no national strategy in sight for people with learning disabilities,

it at least looks like the Transforming Care is struggling on its own terms.

What would I expect to see from these statistics if Transforming Care was

meeting its goals? I would certainly expect to see the number of people being

admitted to inpatient units going down if pre-admission Care and Treatment

Reviews and other measures were having an effect. If people were in the right

place for the minimum period of time, then I would also expect to see the number

of people being transferred between inpatient units dropping. And if people

were leaving inpatient units to go to places with the right support, then the

number of people being readmitted to inpatient units should also be dropping.

Having said

that, it’s obvious that the Transforming Care programme is trying to swim

against a pretty hefty tide – a developing (developed?) catastrophe in

education for children with learning disabilities, ever higher hoops to be

jumped for more thinly sliced social care support, and signs that community

health services generally are disinvesting from supporting people with learning

disabilities at any age. Why do people like Eden have to be the canaries signalling

imminent explosion in this particular coal mine?

Tuesday, 6 March 2018

Dismantling the right support

Today (6th March 2018) @NHSBenchmarking held an

event releasing the findings from their most recent round of data collection

concerning NHS/health services for people with learning disabilities. This is a

project that’s been going for a few years, where volunteer organisations (mainly

NHS Trusts) across the UK help NHS Benchmarking collect information about

health services for people with learning disabilities. I think 47 organisations

took part in 2015/16, and 49 organisations took part in 2017.

I think this project is really important, because it tries

to collect information that isn’t available in any other way (although there is

a strong case to be made that much of this information should be routinely collected

nationally). It also tries to collect information about some of the kinds of

community-based health services that the NHS England strategy Building The Right Support says are needed, if people with learning disabilities or autistic

people aren’t going to keep being unnecessarily shunted into inpatient units.

Thanks to live tweeters at the event (hashtag #NHSBNLD ) I

was able to see some of the findings from this project. NHS Benchmarking also

produced a handy summary for 2017 which you can see here, which they also produced

in exactly the same format (thank you!) for 2015/16, which I found here and is

also shown below. Although the number of organisations taking part changed from

2015/16 to 2017, some of the tweets from the event showed NHS Benchmarking

making comparisons over time so I’m assuming this is OK to do.

This post is just a quick, instant reaction to some of the

information presented today by NHS Benchmarking. I personally think it makes

pretty gloomy reading – rather than building the right community-based support,

these figures generally suggest that this support is being dismantled.

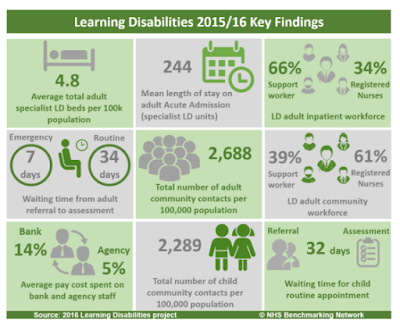

Specialist inpatient

services

The NHS England Transforming Care programme has set great

store on trying to reduce the number of people using inpatient units and

reducing the number of these units that exist. The NHS Benchmarking data (from

NHS Trusts, I think, so it doesn’t include independent sector organisations

that now run inpatient units for half of all people using them in England)

shows that the average length of stay for people in a unit has dropped slightly

from 244 days to 230 days. This includes some general mental health inpatient

units where people stay for much shorter periods of time, and can be contrasted

with the national Assuring Transformation data. For January 2018, this dataset

reported that people spent an average 987 days in their current inpatient unit,

and 1,949 days continuously in inpatient units where they had been transferred directly

between units.

More worryingly, the number of places in these units seems

if anything to be increasing. In 2015/16, there were 4.8 places in these units

per 100,000 of the general adult population – in 2017 this increased to 6.4

places per 100,000 population.

The nursing workforce in these units also changed slightly –

in 2015/16 34% of the staff were registered nurses (66% were support workers),

compared to 32% of staff in 2017 (and 68% support workers).

Across services for people with learning disabilities, in

both 2015/16 and 2017, 14% of the total pay bill was spent on Bank staff. The

percentage of the pay bill spent on agency staff increased, from 5% in 2015/16

to 7% in 2017.

Taken together, this suggests a continuing drift towards

more inpatient services, with a progressively less skilled and stable workforce

working within them.

Community teams for

adults

The NHS Benchmarking project also reported some information on

community teams for adults with learning disabilities that I don’t think is

available anywhere else.

First, the number of contacts with adults with learning

disabilities made by community health services has increased, from 2,688

contacts per 100,000 adult general population in 2015/16 to 2,756 contacts per

100,000 population in 2017. But there are signs that community health services

are ‘doing more with less’, and are creaking under the strain.

For example, the waiting time from referral to assessment

has increased for ‘routine’ referrals from 34 days in 2015/16 to 41 days in

2017. As with inpatient services, the skills of these community teams are also changing

– 61% of staff in these services were registered nurses in 2015/16, compared to

53% of staff in 2017.

Community teams for

children

The NHS Benchmarking project also reports a couple of bits

of information on community services for children with learning disabilities,

and here the trends look pretty catastrophic. In 2015/16 there were 2,289

contacts with children with learning disabilities made by community health

services per 100,000 general child population – a figure already lower than the

equivalent for adult teams. By 2017 this had dropped to 1,471 contacts with children

per 100,000 population, a drop of over a third (36%). Over the same year, the

average waiting time for a routine appointment for children with learning

disabilities increased from 32 days to 72 days.

Dismantling the right

support

The ambition and work of the NHS England Transforming Care

programme (due to finish in a year’s time), particularly in terms of building

decent community-based support services for people and families, is coming up

against the brute reality of disinvestment and cuts to exactly the types of

services specified as needed in Building The Right Support. These cuts aren’t

confined to one year either – the NHS Benchmarking report for 2016 found that

in two years from 2014 to 2016 the number of service contacts with people with

learning disabilities had dropped by 18% and the spend on these services had

dropped by 23%. These cuts seem particularly savage in services for children with

learning disabilities, which is where, if anything, support needs to be

front-loaded.

From an inadequate base, the right support is being further

dismantled.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)