There have been consistent worries and reports about potential discrimination against disabled people who contract COVID-19, both in terms of access to critical care in hospitals and in terms of equal treatment once in critical care. As far as I know, there hasn’t been much focus on whether there is evidence to evaluate the presence or potential extent of such discrimination.

One (far from ideal) way to look at this is by looking at the comprehensive (but inaccessible in terms of easy-read) weekly audit reports being produced by the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC). ICNARC collects and analyses information about people in intensive/critical care with confirmed COVID-19 from 289 critical care units across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. These weekly audit reports (the information I will refer to here comes from their report of 29th May 2020, with information on people up to 28th May) cover in great detail information about who is admitted to critical care with confirmed COVID-19, what treatment they receive, and outcomes (in terms of whether people died in critical care or were discharged alive, and for some measures 30-day survival after admission).

One of the indicators they report on is ‘dependency prior to

admission to acute hospital’. ‘Dependency’ (this measure is not defined) is

recorded at three levels:

- · Able to live without assistance in daily activities

- · Some assistance with daily activities

- · Total assistance with all daily activities

Although it is unclear who decides which category to place

people into, and on what criteria (is it some kind of frailty assessment, as

NICE recommends?), it is the nearest thing I know of to an indicator of need

for support for activities of daily living in these kinds of audits. This

blogpost will simply look at some comparisons between people not requiring

support vs people requiring support, in terms of admission to critical care,

access to health interventions once in critical care, and outcomes of critical

care.

Admission to critical

care

Up to 28th May 2020, the audit reports information on 9,034 people admitted to critical care where there is information on ‘dependency’ (I’m going to call this ‘need for assistance’ from now on). Of these 9,034 people, 8,201 (90.8%) were people with no need for assistance, 802 (8.9%) were people with some need for assistance, and 31 (0.3%) were people with a need for total assistance. The graph shows these percentages, compared to the percentage of people needing assistance admitted to critical care for non-COVID viral pneumonia from 2017-2019.

This graph shows that a smaller proportion of people with COVID-19

admitted to critical care had a need for assistance compared to people in the

previous three years with non-COVID viral pneumonia. There are multiple

potential explanations to account for this difference (COVID-19 might result in

more serious health consequences for a wider range of people across a wider age

range than non-COVID viral pneumonia, for example), but there is clearly a

difference here.

Treatment for people in critical care

Once people are admitted to critical care, what kinds of treatment do people get? The ICNARC audit focuses on advanced vs basic respiratory support and the presence or not of renal (kidney) support.

The graph below shows the proportion of people not needing

assistance getting advanced vs basic respiratory support, compared to the proportion

of people needing assistance getting advanced vs basic respiratory support. As

the graph shows, 75.7% of people not needing assistance received advanced

respiratory support, compared to 57.8% of people needing assistance for daily

living.

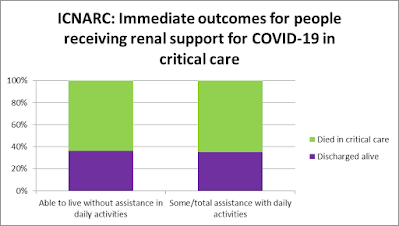

There was a similar difference in people getting renal

support. As the graph below shows, 26.0% of people not needing assistance

received renal support compared to 19.2% of people needing assistance.

Outcomes of critical care

The ICNARC audit records whether people with confirmed COVID-19 who had been in critical care either died in critical care or were discharged from critical care alive. Of course, it is possible that people discharged from critical care could die at a later point, and it is important to note that people who stay in critical care for long periods of time are less likely to be recorded in these figures (because they are still in critical care).

The graph below shows that for people not needing

assistance, 57.8% of people were discharged alive from critical care. For

people needing assistance, 48.3% of people were discharged alive from critical

care.

So far, we have seen that people not needing assistance were more likely to receive advanced respiratory support and/or renal support, and more likely to be discharged alive from critical care. Can we disentangle this a little to understand more about what is happening to people? One thing the ICNARC report allows us to do is to look at these outcomes separately for people who did and didn’t receive advanced respiratory and/or renal support.

So, the graph below reports the same outcomes as the graph

above, but just for those people who had received advanced respiratory support

while in critical care. Of those who had received advanced respiratory support,

48.2% of people not needing assistance were discharged alive, compared to 38.9%

of people needing assistance.

And what about those people who did not get advanced respiratory support and only received basic respiratory support in critical care? The graph below shows this information. For people not needing assistance, the vast majority of people (84.9%) getting only basic respiratory support were discharged alive from critical care. This suggests that, for people not needing assistance, people with a more serious COVID-19 condition in critical care received advanced respiratory support.

For people needing assistance, a much lower proportion of

people getting only basic respiratory support (56.2%) were discharged alive

from critical care. It is unclear why there is this very substantial difference

between people with and without a need for assistance.

There is a similar, if less extreme, pattern for people who got or didn’t get renal support, as the two graphs below show. Among those getting renal support, the proportion of people being discharged alive was very similar for people not needing assistance (36.4%) and people needing assistance (35.2%). Among those not getting renal support, a greater proportion of people not needing assistance were discharged alive (65.3%) compared to people needing assistance (51.3%).

There are clear differences between people needing assistance in daily living and people not needing assistance in daily living when it comes to critical care and COVID-19, according to the ICNARC indicator of ‘dependency’. There are potential differences in access to critical care, differences in access to advanced respiratory support and/or renal support, and differences in outcomes, particularly amongst those people not receiving advanced respiratory support and/or renal support. There are multiple potential explanations for these differences, one of which may be that people needing assistance with daily activities are more likely to be in high-risk groups (for example on grounds of age or health conditions associated with greater risk of a severe reaction to COVID-19). Towards the end of the ICNARC report, the authors report a very useful set of analyses investigating the risk of death within 30 days of entering critical care associated with various factors (e.g. age, ethnicity, area deprivation, body mass index, ‘dependency’) taking all the other factors into account (e.g. the fact that people needing assistance with daily living also tend to be older).

Although as yet only graphs are provided rather than tables of figures, it looks like, for people with confirmed COVID-19 in critical care, if you need assistance with daily living you are somewhere between 1.5 and 2 times more likely to die within 30 days of entering critical care compared to someone who does not need assistance with daily living. This is taking into account age and other risk factors such as obesity. This degree of risk, with the huge exception of age, is as great or greater than any of the other factors investigated in the report (sex, ethnicity, area deprivation, body mass index, immunocompromised, sedated for first 24 hours in critical care).

For all the big differences in access, treatment and outcomes for people needing assistance with daily living that I’ve pulled out of this excellent audit report, I’m not hearing the clamour for rapid reviews, inquiries or action that have rightly been raised when other dimensions of disadvantage have been revealed. Another, material difference as we face the second spike.